- Home

- Matt Young

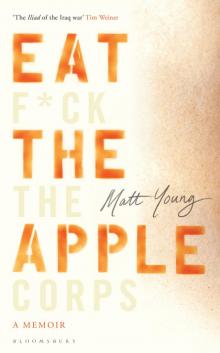

Eat the Apple Page 6

Eat the Apple Read online

Page 6

We itch ourselves awake and shoot our eyes to the walls, indicting the flies, pointing accusing fingers at the small circles of blotchy raised bites, but the flies only do their tiny fly walk and shrug their six shoulders and seem offended we would even suggest they were capable of such a thing.

The game continues for what might be days, maybe years. Inside the husk house days pass like years, but sometimes they pass backward—or up or down. We see Time, a sightless monster made of sand flies with the mouth of a camel spider.

Still, we try to grab it, move Time forward to a moment where this place doesn’t exist, to a moment where the entire desert and everything in it has been turned to glass. When we reach out with our raw seeping hands Time explodes into uncountable pieces and covers the walls and we fall back into hazy fevered sleep. When we wake, our bodies are exposed nerves, itching and bloody and distended and we know the flies are more than the hospitable hosts they’ve made themselves out to be.

The flies are the tide. They are tectonic shift. They are gravity. They break us apart like we are so much kindling, and there is no way to repair the damage they do. The husk house is a terrarium of horror; we are being eaten alive. Our feet and hands split and puss and crust, and sleep does not come. Time is all around us now, its passage unmarkable.

How many hours without sleep, we cannot remember. We burrito ourselves into our poncho liners in spite of the swelter and we sweat and itch and fester. Drink water, says the corpsman. He tells us to change our socks. In the worst cases he gives out Motrin. Somehow it is just us—not the corpsman, not our salts—and we are expected to carry on while our flesh bubbles and rots and bleeds. Our salts make a guard schedule. They overlay patrol routes and continue with life because for them Time has not stopped. For them this is not the husk house of horror, just another patrol base. And so our skin is not the only infected thing—our brotherhood begins to putrefy.

Our salts give us orders and we do not acknowledge. They call our names over and over like overgrown children and we do not answer. We do not ask their permission or their leave, we mutter for them to fuck themselves. We leave our flak jackets open on guard duty, our helmets sit unsecured on our grapes, and our bloated feet no longer fit inside boots so we wear shower shoes. We pray for a barrage of mortars to wipe us away. That’s a way to speed time, we think. Death. Everything in life is waiting to die. We are waiting to die. This is our time, this moment, here on top of the husk house with sweat rolling down our faces, our own stink in our noses. We call on high, beg the Mortar God for indirect fire, and there comes the whistle of our death. We close our eyes and spread our arms messianically as the thunder is called down and the earth shakes and the very foundation of the husk house itself might be cracking and splintering—collapsing like a dying star.

When we open our eyes craters smoke in the distance and the house and everyone inside is still living and breathing. That night we cry ourselves to sleep.

One morning the flies are gone. The flies were winning the fight. We wonder where they are, wonder why they gave up. But over the weeks as Time resettles and becomes again linear for our recovering minds and some of our bodies scar forever we understand. The flies weren’t winning, they won.

Equal and Opposite

An explosive detonates, because that is what explosives are made to do. That is the explosive’s standard operating procedure. The explosive’s SOP. Step one: explosive is built. Step two: explosive is placed. Step three: explosive detonates.

There is little damage to our lead truck, which has triggered the explosive—a blown out tire, some scorching of the steel armor. The explosive was placed too far off the road. We’ll learn later that even small blasts needle into our brains, cause slight compoundable concussive incidents. We never blame the blast—that is only what blasts do.

People are inside their homes, have shuttered their businesses. Only an hour ago the shops were open and bustling, people swept dust from dirt, children sold kerosene like we once sold lemonade.

Our trucks halt, because after a blast that is what we’ve been trained to do. That is our SOP. If a vehicle can push through a kill zone, it does. If it is disabled, it stays put and the subsequent trucks disperse to a standoff distance, check fives and twenty-fives, obtain situational awareness and casualty reports, and assess the situation.

A group of men meerkat in the distance and we stare them down with tiger eyes behind thick bulletproof windows. Charlie, next to me, repeats over and over in his Oklahoma drawl, Motherfuckers, which comes out, Muhfuckers. The rest of us say nothing and when the relay comes over the radio that everyone is five by five we rocket open the doors and pursue the meerkat men, because that is what tigers do.

Now there is a man blindfolded and kneeling on uneven rubble-strewn cratered concrete because that is what we do with the guilty after we catch them. We stand around him in an abandoned room that measures fifteen feet by fifteen feet at Forward Operating Base Black, where we’ve taken him to be interrogated.

We are waiting for the human intelligence exploitation team to arrive so they can question the man. There are two on the team. One is white, the other Arab. This is what I have seen them do to other men: The white man spoke softly in Arabic, he made eye contact, he offered tea and bread. Then the Arab man shouted Arabic. He rolled up newspapers and slapped the men across their faces. Sometimes he used his hands. The white man never stopped his soft speaking.

In the room while we wait for the human intelligence exploitation team, the guilty man attempts to remove the weight from his knees, to settle on his heels. One of us jams a gun muzzle to his spine and moves him back to a high kneel. Behind his blindfold the man whimpers and says, Meestah, please, meestah. We learned the kneeling tactic from John Ta in Third Platoon, who is Vietnamese, and whose father forced him to kneel on grains of rice as punishment when he was young because that is what fathers do.

Into the room walks our Iraqi interpreter, whom we call Rambo because he asks us to and because he carries a large serrated survival knife. Rambo’s skin is the color of whipped chocolate. Muscle striations flex beneath the thin flesh of his jaw, which comes to a pointed chin clad in a soul patch. He paces around the man, boxes the man’s ears, then kneels next to the man and pulls out his knife.

Rambo is not part of the human intelligence exploitation team, for whom we are still waiting. Waiting is most of what we do.

Our circle shrinks as circles do when something bad is about to happen. Rambo presses the knife blade to the man’s cheek and the man speaks quick Arabic. Rambo presses the knife blade into the palm of the man’s right hand, which we flex-cuffed behind his back after we tested it for gunpowder residue. He cuts slowly and the man screams because that is what men being cut do.

We don’t let Rambo take a finger, though that is what he wants to do.

Hours later the human intelligence exploitation team arrives, they speak with the guilty man for five minutes, and the man is found innocent. We drive him back to his home because that is what we are ordered to do.

Outside the truck we snip the flex-cuffs and remove the man’s blindfold and tell him in a language he cannot understand we’ll see him next time and then years later when trying to fall asleep we tell ourselves we did what we had to do.

Masks

We created a person-thing. It looks like us and sounds like us, but it is not us. The person-thing is a by-product—like nuclear waste or babies. The person-thing cannot be uncreated. It is a part of us forever.

Because the person-thing is not human its foremost prerequisite to existence is that we lose not only our own humanity but remove that of our enemy as well. The conditions for loss of humanity were provided amply by the United States Marine Corps.

They said, When I count the cadence you will respond with the repetition kill in a loud bloodthirsty manner. 1. KILL. 2. KILL. 3. KILL.

Hajjis, they said. Muj, they said. Targets, they said.

Do it again, they said. You hesitated, n

ow you’re dead. Do it again. And again. And again. Now do it right.

For the safety of others, we are warned, the person-thing into which we may resultantly transform after the creation of the person-thing should be placed in hermetically sealed packaging, by which is meant deep down inside our brain-housing groups. We are given no repetitions or muscle-memory exercises to create a cell for our person-thing. Much later we will be given a multiple-choice health assessment to judge whether we are us or the person-thing. But the person-thing isn’t stupid. It can lie. We are told it is good to at least warn our loved ones of the person-thing.

The activation of the person-thing is involuntary. It is an act of self-preservation, an autonomic response to external stimuli. The person-thing is not altruistic; it does not want to save us or shield us—we merely hide inside the fallout from the blast that is the person-thing. The fallout is a shell for our past and future to hide inside.

War is our triggering stimulus.

Provoking the autonomic response of the person-thing in war takes an equal amount of dehumanization and anger directed at us by our targets.

In late March 2006 it takes desperation. It takes fanaticism. It takes belief. It takes a white car—an Opel. It takes untold pounds of homemade explosive. It takes an internal trigger—a pressure plate behind the car’s bumper. It takes a collision and a subsequent explosion.

With the application of the external stimulus, the person-thing is loosed. It was frothing in the starting gate and now the shot has been fired.

The person-thing assesses the scene. The engine block of the Opel smolders and smokes on the hood of a Humvee while paint catches fire, flares, and melts plastic and metal alike. In the back of the Humvee the person-thing finds the Opel’s transmission. The driver of the Opel is everywhere. Hair and fingers and feet and fat and skin.

Confetti, thinks the person-thing.

The mounds of things that were the driver are more human than the person-thing. A crowd from a local village gathers and the person-thing yells at them. It doesn’t matter if the villagers do not understand. The person-thing understands.

On its way to confront the crowd of onlookers the person-thing steps into a fleshy pile and stoops to investigate. It is the suicide bomber’s face, blown completely from his skull. It is amusing to the person-thing. The person-thing thinks it is wonderful and hilarious and physically amazing.

It holds the bomber’s face in front of its own and screams at the crowd through plump, blood-flecked lips, watching the crowd’s reactions through empty eyeholes.

The person-thing thinks of this performance as a warning to the villagers. The person-thing hopes the villagers see its smiling face behind the bomber’s rubber one and are frightened.

There is nothing we can do about this. The person-thing returns to its enclosure when it is good and ready. We hide in our shell and wait.

Years later, we discover a picture of the scene hidden away in a box of memories. We feel sick to our stomachs and our legs become restless. We think we need to find a dog to stroke, a baby to coddle. We destroy the picture and reinforce the packaging that houses the person-thing with positive thoughts and exercise and whatever other coping mechanisms we have developed. But even as we rip the picture to shreds and our eyes well with tears for our once-lost humanity, we feel the person-thing slithering along the walls of its makeshift cell, waiting.

Riding the Gravitron

First we are patrolling in our Humvees: Main Supply Route Boston to Alternate Supply Route Iron—I lose track of brown houses and dirty sheep. I am in the lead truck with MacReady, Fredericks, and Sherburne. They needed a dismount. I am sitting behind Fredericks, who is driving. Sherburne is on the gunner platform. From shotgun, MacReady halts the patrol every once in a while to get a better look at some suspicious trash or a dead dog in case of IEDs. We are smoking and talking about maybe quitting.

Then there is noise, but not noise like construction-going-on-outside-of-my-window noise. It is all-around noise. Noise that feels at once everywhere and nowhere. Maybe I’m imagining it. It could be a dream, I think. Like one of the ones that feels like falling and then I wake up at a desk or a table or in my bed, jolting so hard the entire world notices. In what might be my dream my eyes are closed, but not like they’re closed in the daytime, when light shines through the thin membrane of my eyelids and gives the dark an orange-rose tint. It’s black as pitch behind my eyelids. That’s impossible, I think, or maybe it is possible because it is a dream and I really am asleep and that noise is the jolt that’s going to wake me up and I’ll be back at the patrol base, maybe having fallen out of bed.

That doesn’t seem so bad.

We were going to quit smoking.

There’s this feeling of weightlessness, too, like being inside the Gravitron I used to ride at the Fireman’s Carnival during summers when I was a kid.

And then a blur of things coupled with queasy stomach flip-flops, and I wake up at an aid station, a large one-room tent, partitioned by plywood and paper curtains. I lie on a gurney atop a starchy sheet while Navy doctors cut off my clothes and my boots. I try to tell them, Stop, those are my favorite pair of boots. But they cut them anyway.

It’s April and starting to warm up, but we’re inside and there’s air-conditioning. I’m cold. It feels unnatural, like how people must’ve felt the first time they saw electric light. My back hurts, my right arm hurts, my head hurts, my right leg hurts.

So, it hadn’t been a dream and the noise wasn’t part of the jolt that would wake me up and I wasn’t weightless because I was riding the Gravitron with my friends, but because—I later learn—our Humvee was flipping upside down. Sixteen thousand pounds of ammunition and engine components and equipment and up-armored steel and people rolling and flipping down a cracked and decaying road in the southern desert outside Al Fallujah.

A male nurse asks me questions, and pushes different places on my belly.

He asks, What’s your name? What happened? Where are you? Do you feel nauseated? Did you throw up?

I answer, Matt Young. I don’t know. Iraq. Yes. Yes.

I tell him, Turn off the AC. I’m cold.

He jams an IV into my left arm and walks away.

MacReady, my vehicle commander, is the only other person from my truck in the room with me. He’s on a cot to my right. A female nurse pushes on his abdomen, and asks the same questions my nurse asked me. MacReady smiles at her, says something I can’t hear, the nurse laughs. I watch his hand sneak behind her back and pinch the middle of her left buttock. She swats him away, laughs again, and leaves.

Goddamn, Young, he says. We picked the wrong job.

He tells me after the IED Fredericks and Sherburne got casevaced elsewhere: Fredericks to surgical for brain scans, and Sherburne to Germany. He ain’t coming back, MacReady says.

We lie there in silence for a few moments, and I let those words sink in. I just want to smoke, but then thought of hot tar in my throat makes me gag. My head’s swimming, the queasy feeling before everything blurred returns, my teeth chatter. I need to call home, I think.

They’re going to have to check us for internal bleeding, MacReady says. Hope you washed your ass recently.

What?

It’s the easiest way for them to see if you’re scrambled up inside. Fractured tailbone’s hard to diagnose; it’s just quicker than waiting to see if you shit blood, he says. It ain’t so bad. Hasn’t your girl ever snuck one by you? Hell, I always act like I don’t like it, but she knows I do.

MacReady keeps talking about anal stimulation during sex. I hear him, nod and laugh at the right times, but I’m just watching the drip from the IV, feeling the saline flow into my vein.

It’s cold like the rest of the room, taking the heat right out of me. The queasy feeling comes in waves.

Before I passed out I was holding Sherburne’s head between my knees, trying to stabilize his cervical vertebrae. Our corpsman had taught us that before deployment. Most everyone mad

e some sort of tea bag joke. We’d all laughed.

Sherburne had been thrashing on the road when we’d found him ten meters from the Humvee. The blast had smashed his face into the spades of the fifty cal, and thrown him from the gunner’s turret. Half his forehead was hanging down over his right eye, I could see the whiteness of his skull. He kept hitting himself in the face, screaming, trying to put words together that didn’t make sense. So I put my knees on either side of his head and MacReady held his arms down and talked to him and tried to make jokes, let him know everything would be all right. I tried to soak some of the blood off his face, take care of the cuts and scrapes, tried to do the first-aid I’d been trained to do. When I touched his face, it felt crunchy, the skin dented in and stayed that way, like a Rice Krispies Treat.

There are footsteps. The male and female nurses are back.

For all his talk, MacReady begins yelling about how they’d better not put anything in his asshole.

They look confused. They tell us we’re free to go. They’ve brought us new cammies and boots. The clothes are clean and don’t fit quite right; there are no salt lines or bloodstains, no dust, no mud from fallow fields cakes the knees of the trousers. Like the past months have been erased. I ask for my old clothes. They tell me they’ve already been incinerated. MacReady asks the woman for two cigarettes. When she turns, he again pinches her butt cheek. She doesn’t look back.

Goddamn, he says. We’re in the wrong fucking job.

Revision

On May 21, 2006, Benito “Cheeks” Ramirez is manning the turret when his Humvee rolls over a pressure plate attached to a surface-laid one-five-five round on Main Supply Route Michigan and he dies.

The driver and three passengers are wounded. Our battalion sergeant major, whom we call Iron Mike, loses use of his right eye.

Eat the Apple

Eat the Apple